Backward design is a framework for planning a lesson, a module, or an entire course. The term was introduced to curriculum design by Jay McTighe and Grant Wiggins in their book Understanding by Design (2005).

In backward design, assessments, instructional and learning activities, and feedback are aligned with learning objectives for an entire course, a module, or an individual lesson. Instructors who use backward design often start by establishing or reflecting on given learning objectives of a lesson. They then proceed “backwards” to create assessments in which students can demonstrate what they have learned. The next step is to create learning activities and instructional materials in alignment with the learning objectives.

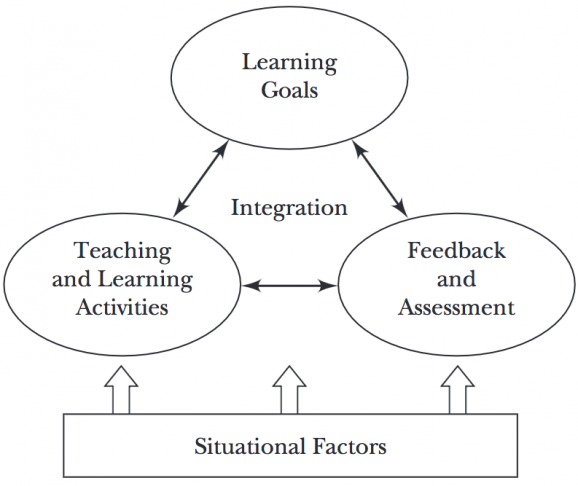

Fink (2003) proposed an “integrated course design” that extended the basic idea of backward course design by integrating situational factors into the process of creating aligned learning goals, activities, and assessment. The situational factors help identify the context of the course. Therefore, “integrated course design” seeks alignment between the course components embedded in the course context.

How to Implement Backward or Integrated Design, Step by Step

Step 1: Identifying situational factors

Carefully consider what contextual elements influence your course, and your student’s learning. How is your course structured and delivered, what is the subject matter, student characteristics, your own capabilities, institutional expectations, as well as the broader societal circumstances? All of these factors should be carefully considered when designing a cohesive learning experience.

Step 2: Developing learning goals and objectives

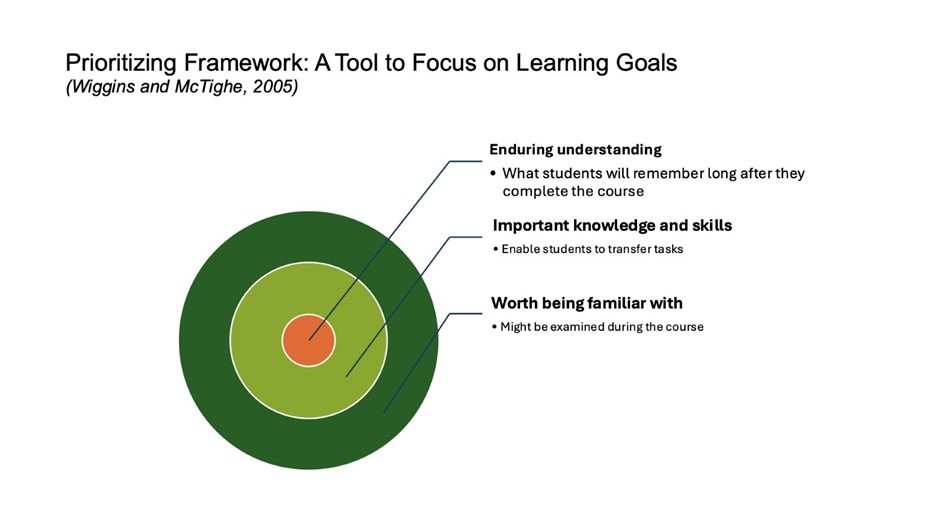

Write your learning goals for the course, which are the general statements of what you would like your students to learn and retain after completing this course. You can use the Prioritizing Framework Tool to establish priorities around the big ideas you have for what students will learn in your course:

To create effective learning goals, it is important to consider several dimensions (Fink 2013) of learning such as:

- Applications (e.g., what kinds of thinking are important for students to learn how to do in this course?)

- Integration (e.g., what kinds of connections should students be able to make between ideas in the course?)

- Human dimensions (e.g., what should students learn about themselves and others from this course?)

- Caring (e.g., what changes should students adopt from taking this course?)

- Learning how to learn (e.g., what should students learn about how to learn from this course?)

- Foundational knowledge (e.g., what information is important for students to understand and remember for this course?)

Note that while you may have difficulty realistically including all six of these dimensions, the more of these dimensions that are included, the more supported each of the other dimension will be.

The learning goals could also help you write more specific and measurable learning objectives that indicate what the students will know or be able to do at a certain time of the course. Therefore, you may write what students should know and be able to do by the end of the lesson. Upon completing a lesson in your course, or by the end of the semester, what knowledge, skills, or abilities should your students have learned or mastered?

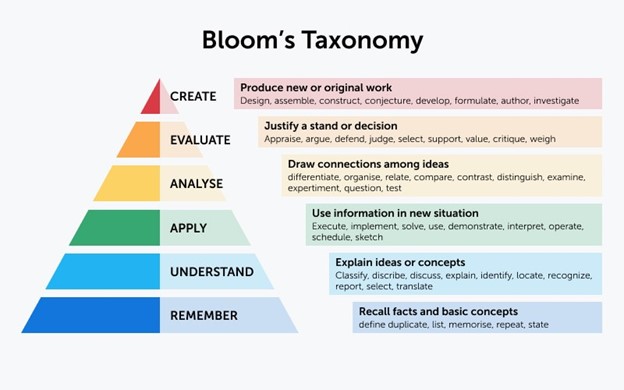

You can use Bloom’s Taxonomy as a tool identify the learning aspect, you’d like the students to develop and experience and write measurable and specific learning objectives for them.

Above graphic is released under a Creative Commons Attribution license from Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching.

Step 3: Creating assessment plans

Reflecting on learning objectives, identify the assessment tools and strategies that could help demonstrate how students have achieved those objectives. What is acceptable evidence? What documentation do you need to evaluate students’ progress toward proficiency of the learning objectives and course goals? How will students demonstrate their learning? When deciding how to assess student work and what feedback needs to be given, it’s important to think in a forward-looking way. This means that assessments and feedback revolve around what students should be able to do with the course content during or after the course or a unit of it is completed. The course goals are a crucial guidepost to help identify what assessments should explore. Regardless of the goals selected for the course, these expectations and standards should be clearly articulated to students.

In addition to instructor’s assessment of student learning, self-assessment is an important process for students to engage in. This may start as scaffolded group activities to get students to reflect on their performance and learning of material, eventually progressing to individual reflective practice.

Frequent, timely feedback is essential for fostering student understanding of course expectations and to help students better develop self-assessment skills.

Step 4: Identifying or developing learning activities

Create a sequence of steps (activities?) which are aligned with learning objectives and assessments and set the students for success in their course experience. What activities and direct instruction will you provide to support students’ learning towards course goals? How will you scaffold the learning process? What activities and materials will you use to move your students progressively toward self-directed learning (Brookfield 2009)?

Once you have worked through these steps, make sure that objectives, assessments, activities, and materials align with each other to support the desired learning outcomes. Alignment in this context is the extent to which learning objectives, assessments, activities, and instructional materials work together. Learning objectives should inform and determine formative and summative assessments in the course or lesson. Learning objectives and assessments will then determine which materials, activities or lectures are used to support learning towards the desired objectives. Once instructors have decided on how to assess student learning and for what purpose (i.e., learning goals), the next step is to design learning activities that help students reach those goals. One way to think about learning activities is to try to have each learning activity cover at least one of three different types of activities:

- Getting information and ideas (e.g., lectures, engaging with primary and secondary sources)

- Experience (e.g., direct activities in authentic settings/scenarios, direct observation of phenomena, case studies)

- Reflective dialogue (e.g., reflective journaling, discussions)

Step 5: Integration/Realignment

The final stage of integrated course design is to “put the pieces together,” that is, to develop the structure of the course. This is to be done while considering the building blocks of situational factors, learning goals, assessment and feedback procedures, and learning activities. Traditional course design has relied on alternating lecture and reading activities, followed by a culminating test. This course structure primarily only reinforces the “getting information and ideas” mode of thinking. Integrated backward design provides opportunities for instructors to create meaningful pathways for student learning with a variety of structures and approaches attuned to the goals and context of the course. While this integration step marks the end of one iteration of course design, because of the shifts that occur in context, content, and goals, courses should be reexamined and realigned to ensure that they are achieving their goals each time that they are delivered to students.

FAQs

Wouldn't it be faster just to do lesson planning on its own?

In the short term, it may feel like simply planning a lesson divorced from larger goals may be a quicker way to create courses. However, creating a course in a piecewise way often leads to difficulty in reaching course objectives, courses that are too difficult or too easy for the students that are enrolled, and may lead to more work in between semesters due to these issues. Investing the time upfront in creating an aligned course can thus eliminate many of these issues and save instructors time in the long run.

Isn't backward design just 'teaching to the test?'

Although backward design may seem like “teaching to the test,” backward and integrated design do not imply that you should be teaching students exactly what answers they will need to use on some exam in the future. Rather, backward and integrated design are about determining the most important tools and knowledge that a student should have to be considered proficient with the course subject and evaluating whether or not they meet those standards. Without considering these important facets upfront, students may end up leaving a class without a coherent framework with which they can engage in the course material.

What's the difference between course and syllabus design?

While syllabus design is undoubtedly part of the whole course design process, there are many more pieces to a course than just designing a good syllabus. A syllabus can be thought of as the manifestation of good course design, since its purpose is to establish the goals, assignments, assessment procedures, philosophical underpinnings, and structure of a course. Without these course design elements, a syllabus on its own cannot be an effective means of delivering the “what,” “why,” and “how” of a course.

Is there a fixed ‘entry point, when designing a course using Integrated Course Design?

No, there is no fixed "entry" or "exit" point when designing your course using this method. For example, some instructors will already have been given a set of learning goals, while others may have to use specific assessment methods. Even in these cases, learning goals, teaching activities, assessment, and situational factors can be brought into alignment by working "backwards" from pre-determined factors (in this case aligning learning goals and activities to the given method of assessment, or matching learning activities and assessment to the pre-determined learning objectives).

What are some examples of situational factors?

- The course context (e.g., number of students in the course, course level, expectations of the university/department for the course, etc.)

- The nature of the course content (e.g., is the course more theoretical or more applied, is there controversy within the field on this topic, etc.)

- Characteristics of the students (e.g., prior knowledge, goals and expectations, life situations, etc.)

- Characteristics of the instructor (e.g., beliefs and values, knowledge of subject, teaching strengths and weaknesses, etc.)

What if I have other questions about course design?

If you have other questions about designing courses, please check out our other resources on the Center for Teaching website; alternatively, feel free to reach out to the Center for a consultation!

References

Select Bibliography

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook I: The Cognitive Domain. New York: David McKay Co Inc.

Brookfield, S. (2009). The concept of critical reflection: Promises and contradictions. European Journal of Social Work, 12(3), 293-304. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691450902945215

Fink, L. D. (2003). Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to designing college courses. Jossey-Bass.

Fink, L. D. (2013). Creating significant learning experiences. John Wiley & Sons.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J, (2005). Understanding by design (2nd ed.). Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.