In this special guest contribution, 2024-25 Graduate Teaching Fellow Kit Fynaardt (Mathematics) offers a reflection on his experiences as learner and as a teacher, highlighting the value of intellectual empathy.

Intellectual Empathy: A Definition

“I have a lazy class this year.”

“Students just don’t try anymore.”

“I showed them this problem yesterday, I don’t understand how they can’t get it right.”

Phrases like these are spoken by teachers who are frustrated with their students. And the feeling is understandable. Trying to teach a room full of novice learners is a unique challenge. However, such phrases can lead to more harm than good. It can be helpful to try replacing such phrases with:

“My class this year requires more repetition of definitions.”

“Students have access to knowledge, but they can’t apply it yet.”

“My students have seen the method, but they don’t know the context.”

Reframing these and similar classroom issues with intellectual empathy can reveal ways to help reduce frustration for yourself as an instructor and your students. In Freedom to Learn, psychologist Carl Rodgers emphasizes the importance of empathy in the classroom: “A high degree of empathy in a relationship is possibly the most potent factor in bringing about change and learning...when the teacher has the ability to understand the student’s reaction from the inside, has the sensitive awareness of the process of how education and learning seems to the student… the likelihood of learning is significantly increased.” Rodgers argues that an instructor’s ability to see their classroom from the students’ perspective is a critical element for both effective teaching and effective learning to occur.

As I’ve found it useful to imagine, intellectual empathy is a subset of this concept that is often particularly useful in teaching novices. I think about intellectual empathy as putting yourself in the shoes of someone who doesn’t yet understand. This resource is designed to point out frustrations for both students and instructors that can be alleviated by practicing intellectual empathy.

I am a graduate student in mathematics. This makes me a math student and a math teacher at the same time. I have observed that my peers and I might criticize a professor’s teaching choices and then turn around and make similar decisions in our own classrooms. I remember being frustrated when a professor left a comment on an incorrect homework problem, exclaiming “I showed this in class!” Certainly they can’t expect me to master a problem instantly after seeing a single example in class, I thought. And yet I caught myself the very next day exasperatedly telling another graduate student that I couldn’t understand why my calculus students were struggling with their first derivative assignment when I showed them all the problems in class! These are both examples of the frustrations that intellectual empathy can help reduce.

Strategies for Intellectual Empathy

Intellectual empathy can take the form of sweeping changes to a course or small day-to-day strategies. Find below some strategies I have tried for applying intellectual empathy in various aspects of teaching. Some important principles include transparency, defined as making the what and why of teaching decisions clear to students (Winkelmes, 2019), and using teaching strategies that help all students access course content equally (Addy, 2021).

Respond with kindness and generosity:Avoid phrases like “This is an easy one!” “Obviously…” and “Of course…” This kind of rhetoric can alienate students who find the class difficult, making them feel like they are the only one of their peers who doesn’t “get it.” Instead, explain why the current content is important. Example phrases include “This is a classic example of...” “This follows from our previous work by...” or “This is a core definition you will definitely need later...”

Avoid assumptions:When discussing classes or students with others, be careful when attributing poor performance to a lack of effort or care. Most students have jobs, more classes, or other priorities that may be taking up their time and energy. Students may be trying as hard as they can to succeed in your class; encourage students to try approaches that may help them rather than make assumptions about why they are struggling. I’ve found it effective to try phrases like “My class this year requires more repetition of definitions, and that’s OK.” “Students have access to knowledge, but they can’t apply it yet.” “My students have seen the method, but they don’t know the context.”

Be transparent about what learners can expect:Communicate with students about policies such as attendance and deadlines and be upfront about how flexible they are. Some instructors don’t have the space in their own schedules to be flexible with deadlines, so be clear with students when this is the case. This can help avoid feelings of frustration and “unfairness” when deadlines can’t be moved.

Use strategies that encourage and include novice students:

- When previously provided definitions are needed for a new concept, provide regular access to them: have a definition bank on ICON students can refer to, repeat them at the beginning of every class, or ask students to share them through retrieval practice.

- When first explaining a topic, show simple examples that don’t have exceptions or caveats.

- Don’t introduce new ideas or concepts right before a major assessment like an exam.

- Repeat yourself without frustration so the students hear key ideas many times.

- Scaffold student learning by providing opportunities for practicing. In math, for example, include multiple practice problems for each concept on relevant assignments.

- Provide opportunities for students to check in early and often with their learning so that you and they better understand classroom experience and learning. This might take the form of low-stakes assessments like quizzes or homework, or even just asking students to fill out a notecard during class with one thing they need more support with.

Approaching Teaching Novices with Intellectual Empathy

I remember a day when I was teaching College Algebra, a particularly frustrated student asked “Why do we have to know all these definitions and formulas? Why can’t you just show us exactly what we have to do for the homework?” My gut reaction was to respond with similar frustration. Are you kidding me? Do you think in a real job your boss is just going to tell you “exactly what you have to do” all the time?But I had just been in a similar situation as a student in my own classes, wondering why we spent all of class discussing theorems when the homework problems were mostly calculations. I realized it was an issue of the expert-novice divide.

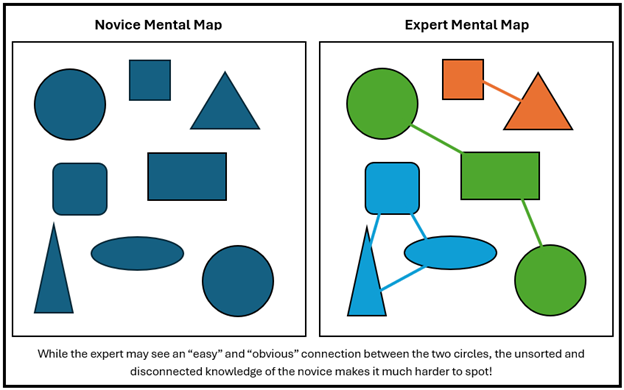

This student saw my math class as a series of problems that each had a unique solution process, totally disconnected from each other problem. They wanted me to simply add another process to the list and move on. It was only through my more experienced eyes that I could see the connections between all the definitions, formulas, and homework problems. So instead of responding in my own frustration, I explained, transparently, why class was structured this way. “Your future job might have a day of orientation, maybe a week. And then you’re going to work at that job for a year, five years, maybe longer. It is impossible to train you exactly how to do every single task that your job will require during orientation. So instead, you have to take the tools you have been given during orientation, ask questions of your peers and higher ups, and figure out each new problem as it comes. That’s what I’m trying to teach you here. I don’t want to give you a list of solutions for every problem in my class, I want to give you the tools you need to figure it out for yourself.” I tried to explain to the class that I wanted them to become experts and not stay in their novice way of thinking. Without intellectual empathy, this situation could have spiraled out of control into more frustration for everyone.

When asking students to attempt a beginner-level problem, a professor may be tempted to give encouragement in the form of “this is an easy one!” But this phrase can cause more harm than good because of a subtle miscommunication. Students are novices and are therefore “organize knowledge as a list of facts, formulas, or heuristics (Persky 2017). They view beginner-level problems as serious tasks requiring intense mental effort. Hearing the problem is “easy” from the professor’s perspective may inspire doubt in their abilities and create the impression the rest of the class understands the problem, an alienating experience. Continuing the practice of intellectual empathy can help avoid these unintentional miscommunications.

Approaching the classroom and your students with intellectual empathy can help bridge the expert-novice divide and ease frustration and miscommunication between instructor and student. Try practicing intellectual empathy in your own class and the benefits will be clear.

Further Reading

- More on the expert-novice divide.

- Cognitive load theory and the expert-novice divide.

- Instructor and student perceptions of teacher empathy.

- Empathy as teaching for student success.

References

Addy, T. M., Dube, D., Mitchell, K. A., & SoRelle, M. (2021). What inclusive instructors do: Principles and practices for excellence in college teaching (1st ed.). Routledge.

Carter, R. E. (2015). Faculty scholarship has a profound positive association with student evaluations of teaching—Except when it doesn’t. Journal of Marketing Education, 38(1), 18–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475315604671

Feldman, K. A. (1987). Research productivity and scholarly accomplishment of college teachers as related to their instructional effectiveness: A review and exploration. Research in Higher Education, 26, 227–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00992241

Persky, A. M., & Robinson, J. D. (2017). Moving from novice to expertise and its implications for instruction. Carolina Digital Repository (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill). https://doi.org/10.17615/vj75-5w07

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14.

Rogers, C. R. (1969). Freedom to learn: A view of what education might become. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA00554764

Winkelmes, M.-A., Boye, A., & Tapp, S. (Eds.). (2019). Transparent design in higher education teaching and leadership: A guide to implementing the transparency framework institution-wide to improve learning and retention (1st ed.). Routledge.